A lot to learn from Norway's land use

A recent visit to Norway by Trees for Life field staff had a primary research question: to what extent is the lack of woodland and montane scrub in Scotland due to natural processes or is it determined largely by land use history and current practices?

A recent visit to Norway by Trees for Life field staff had a primary research question: to what extent is the lack of woodland and montane scrub in Scotland due to natural processes or is it determined largely by land use history and current practices?

I’ve never been to Norway before but there has been a proposal for a visit by the Montane Scrub Action Group for some years now. We were spurred into action by Duncan Halley, a Scot who’s been working for the Norwegian nature conservation agency NINA for the past twenty years. Duncan has been inspirational in researching information on geology and climate in similar areas of both countries, allowing good comparisons to be made regarding the relative extent of woodland cover. Our main research question … to what extent is the lack of woodland and montane scrub in Scotland due to natural processes or is it determined largely by land use history and current practices?

Thus a group of 15 of us, 7 from Trees for Life and 8 from a range of other organisations, set off to meet up with Duncan at Stavanger airport. Driving west to Fitjadalen, it was immediately apparent just how much native forest there is in Norway. It’s not always been like that; this land was as deforested as Scotland in the recent past. Following large scale emigration and land abandonment in the mid 19th century, the forest has returned. Subsequent low numbers of browsing mouths has allowed an exponential regeneration of trees from the coastal zone up into the mountains.

Our first hike that day took us steeply uphill, at times using chain handrails to scale great slabs of rock, to a viewpoint over the spectacular Manafossen waterfall. Dropping 90m this is ranked as the third best waterfall in Norway (see here); I’d like to see the others!

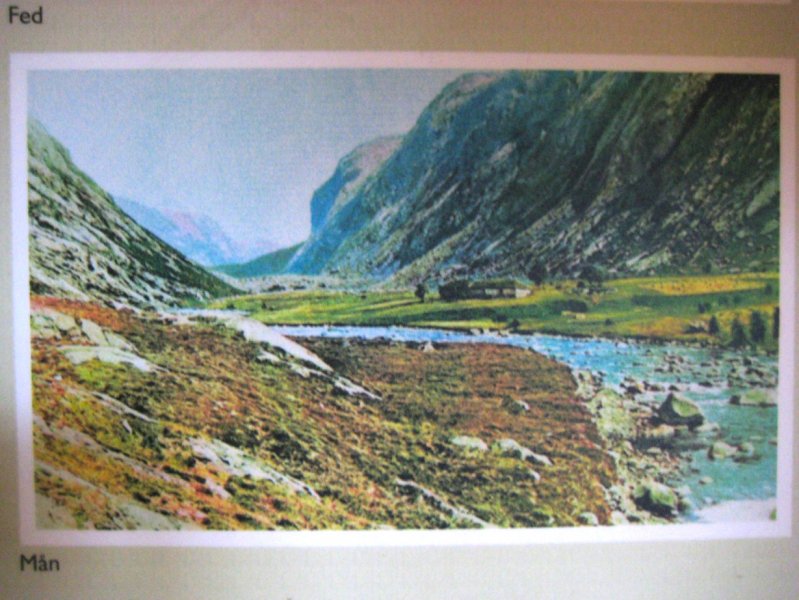

In the hanging valley above, we stayed for two nights at the old farmstead of Man, now converted into a basic but comfortable bunkhouse. Whereas Manafossen below us was wide and thunderous, the old farm sits beneath a narrow waterspout running down the cliff face behind. This place was occupied by two sisters and their families of eleven children in the late 19th century, both husbands dead. Respect! Every day must have been a prayer.

A picture in the hostel showed the valley in 1927. In contrast today, there are trees on all the slopes, mainly birch, up onto the craggy mountain tops; very few Scots pine, possibly completely removed in the past we conjectured.

Next day, with heavy rain, we walked up the valley, crossing a huge boulder moraine damming the lake above and climbed uphill through the forest of birch, rowan and aspen, up onto the plateau above. Here amongst deep snowy patches we found a treeline of scrubby windswept birch, willows and juniper. We disturbed willow grouse, still half white from winter; a male ring ouzel sang. Hey this place looks just like Scotland with trees! Duncan had chosen the location as a direct comparison with the western highlands, with gneiss geology and climatically very similar to our project area.

The following 3 nights we spent close to Hovden, in the county of Bykle. Here the landowner had converted the old family farmhouse and barn into sumptuous accommodation. We were up at about 900m, on the edge of the snowline, with frozen lakes and a lot of ground still covered; this year has seen unprecedented late snow in south-west Norway and although our trip had been timed to see trees in leaf, everything was late. The surrounding land was a wildlife haven, with all the animals and birds concentrated around here where there were some patches of open ground and water. Flocks of fieldfares in nesting mode, black grouse chortling away, golden plovers in breeding plumage, a crane on the open water, mountain hares bounding about, even foxes openly about in the evening. Walking out that first evening we were buzzed by a merlin; and I saw my first bluethroat! This bird, very characteristic of the treeline/scrub zone, was probably waiting for warmer conditions to go higher to breed. Some folk tramped uphill through the deeper snow and were rewarded to see a group of reindeer silhouetted against the skyline in the late evening light.

Duncan had chosen this area as a good comparison with the Cairngorms …. granitic geology, with similar rainfall, wind speeds and temperature patterns. Our day in the Scots pine forest of Berdalen indeed felt like walking up through Glenmore. This is a big landscape, forested now, but again with an earlier farmed history. A few granny pines stand as testimony to time, but most pine has regenerated within the last 50 years or so. It was just like Scotland … the pines, birch, aspen, willows, areas of open bog and wet heath, burns to cross, anthills. Except there were piles of moose pellets and lots of capercaille droppings; some folk flushed caper at one point. Occasional Norway spruce are found through the forest, at higher elevation then the pine, up into the birch zone.

Duncan had chosen this area as a good comparison with the Cairngorms …. granitic geology, with similar rainfall, wind speeds and temperature patterns. Our day in the Scots pine forest of Berdalen indeed felt like walking up through Glenmore. This is a big landscape, forested now, but again with an earlier farmed history. A few granny pines stand as testimony to time, but most pine has regenerated within the last 50 years or so. It was just like Scotland … the pines, birch, aspen, willows, areas of open bog and wet heath, burns to cross, anthills. Except there were piles of moose pellets and lots of capercaille droppings; some folk flushed caper at one point. Occasional Norway spruce are found through the forest, at higher elevation then the pine, up into the birch zone.

We had lunch up at the mountain hut of Berdalsbua at around 1050m. Norway is very civilized in many different ways, not least in its hut network. Providing comparative ease and luxury for the walker, we found a fully stocked larder, a gas cooker, woodstove with fuel, compost toilets, even duvets on the bunks. Payment is retrospective on an honesty basis. I’ll be back!

Climbing higher up above 1100m we were now in the true scrub zone with wind blasted, snow damaged downy birch, juniper, patches of dwarf birch and montane willows, bearberries and crowberry. The botanists ‘oohed’ and ‘aahed’. A pair of eagles were spotted gliding along the distant crags opposite; comments and reflections on how these birds don’t need the open mountain landscape they’re associated with in Scotland. Our final 2 days were spent on the coast at Bomlo, where we were hosted by the Hordaland provincial environment staff. No snow down here, but the spring was still late.

Climbing higher up above 1100m we were now in the true scrub zone with wind blasted, snow damaged downy birch, juniper, patches of dwarf birch and montane willows, bearberries and crowberry. The botanists ‘oohed’ and ‘aahed’. A pair of eagles were spotted gliding along the distant crags opposite; comments and reflections on how these birds don’t need the open mountain landscape they’re associated with in Scotland. Our final 2 days were spent on the coast at Bomlo, where we were hosted by the Hordaland provincial environment staff. No snow down here, but the spring was still late.

Firstly we visited the Anuglo reserve, a series of offshore islets with underplanted pine forest now being restored, familiar work with the removal of ‘exotic’ plantation trees. More unusual, and very different for us, the base-rich outcrops host a range of other trees, including yew. We had a group photo beside the largest ivy in Scandinavia, its trunk grasping the rock face, before spreading out in branches a few metres above our heads.

Firstly we visited the Anuglo reserve, a series of offshore islets with underplanted pine forest now being restored, familiar work with the removal of ‘exotic’ plantation trees. More unusual, and very different for us, the base-rich outcrops host a range of other trees, including yew. We had a group photo beside the largest ivy in Scandinavia, its trunk grasping the rock face, before spreading out in branches a few metres above our heads.

Next day we were hosted by the mayor and kommune of Bomlo. Our first stop was a coastal heath site, reminiscent of the western isles, a cultural landscape that the community are keen to see remain as open ground. Next a calcareous pinewood, unusual for us to see Scots pine growing with hazel and ash and a rich carpet of spring flowers.

The locals were interested in our visit, and after lunch speeches were made, gifts exchanged. That afternoon we spent around the offshore islands, ferried around expertly, regenerated pine forest everywhere. Sea eagles nest here, one lucky boatload of folk getting a good view.

It’s important to say that the forested landscapes of Norway still support a lot of people, many more than in the rural areas of Scotland. Landholdings are much smaller, extended families often managing small farms with areas of forest, building houses from local timber, using woodfuel, hunting and fishing for their own use, with employment opportunities available locally because there are still thriving local communities. Could Scotland move towards a similar model?

Driving back to Stavanger airport next morning, we’d already grown used to abundant forest so it felt unusual to see open fields and heathland. This area is predicted to become forested over the next few decades, and indeed some is now in the early successional stages of change. Locals at Bomlo had told us how they feel there is too much forest! A very different situation to Scotland. Our general conclusion … although the Highlands and west coast of Scotland have probably been more thoroughly deforested, and perhaps for longer periods than south-west Norway, there’s one main reason we have comparatively little native forest … land management, specifically for deer and grouse. Will we live long enough to see this change?

It’s important to say that the forested landscapes of Norway still support a lot of people, many more than in the rural areas of Scotland. Landholdings are much smaller, extended families often managing small farms with areas of forest, building houses from local timber, using woodfuel, hunting and fishing for their own use, with employment opportunities available locally because there are still thriving local communities. Could Scotland move towards a similar model? Coincidentally on returning home, journalist and writer Lesley Riddoch came to speak here at Findhorn the following week. She believes we have a lot to learn from Norway (see here). I think I agree.