Category: Volunteer Voice

We’re thrilled to feature a guest piece written by one of our incredible volunteers, Alice Melvin, who participated in a Trees for Life Rewilding Week in Glen Affric in September 2024. In her reflection, Alice shares what inspired her to volunteer, the power and pleasure of building connections in nature, and the value of learning and gaining fresh perspectives through hands-on experience.

It’s late September and I’m bumping along a single-track road in a minibus with nine strangers. I’m feeling the churning mix of excitement and apprehension that accompanies all steps into the unknown. We’re heading to Glen Affric to spend a week volunteering with Trees for Life, an organisation whose pioneering rewilding work I have followed for a long time.

I am someone who worries a lot about the climate and biodiversity breakdown and I’ve found that the best way to deal with this anxiety is to involve myself in practical projects that are making a positive difference. So the opportunity to spend a week working outdoors with such an inspiring and hopeful organisation felt irresistible.

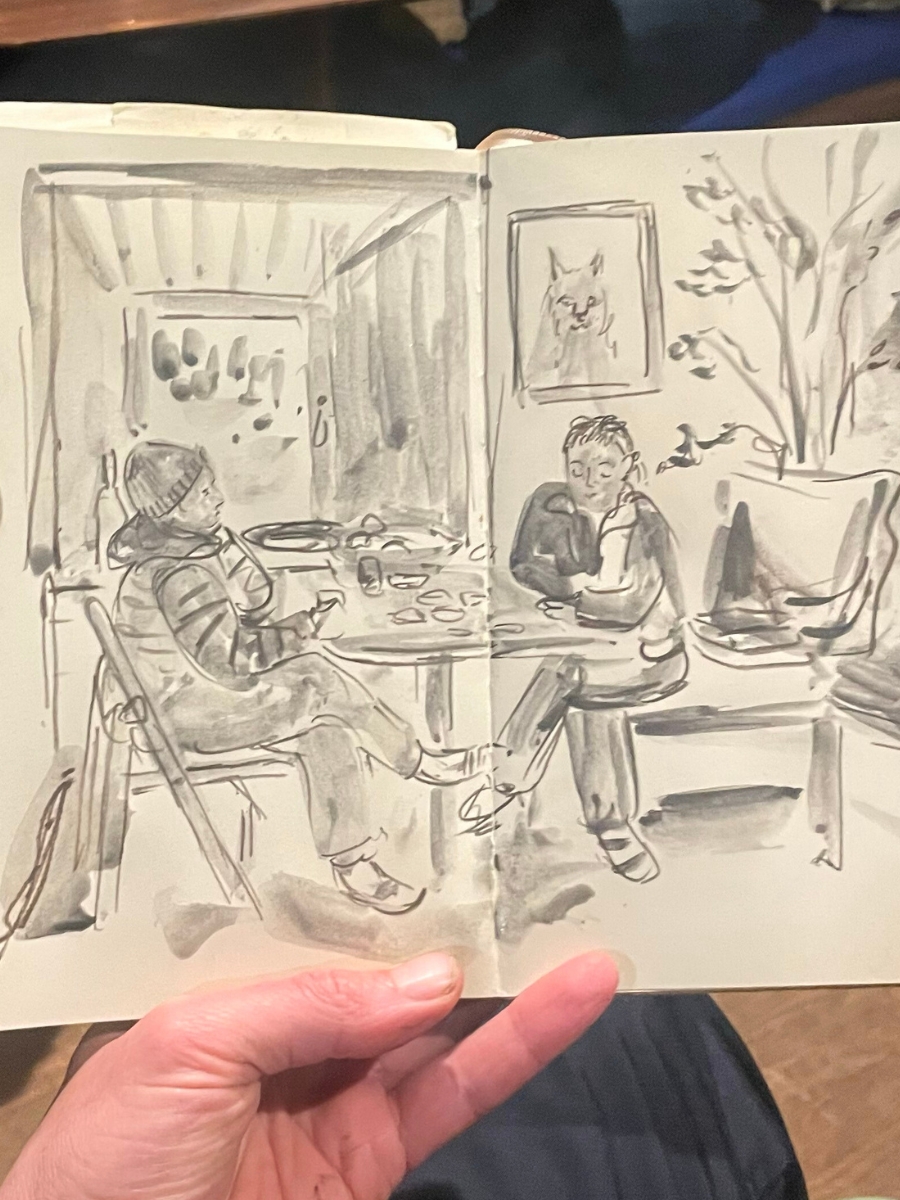

In recent years, time outside in nature has become increasingly important to me and my work as an illustrator. In 2019 I was caught up in a traumatic bereavement and amid the disorientating turmoil of grief I discovered that it was sketching outside in wild green spaces that helped calm and ground me. The process was transformative, leading to a profound shift in my work and how I manage my mental health. Drawing outside has remained a place of peace and inspiration for me ever since.

So here I am, watching the beautiful view roll by through the minibus window, chatting with the other volunteers and beginning to feel myself relax into the experience. We’ve had a final pit stop at a corner shop and sent farewell text messages – we’re heading out of range into the wild, and it feels good.

Our accommodation for the week is Athnamulloch, an old crofter’s cottage now transformed by Trees for Life into a cosy bothy nestled in the heart of Glen Affric. Stepping outside I feel held by the cradling presence of the surrounding mountains. There’s no phone signal or Wi-Fi here, the power comes from the solar panels, and our water needs to be collected daily from the nearby beck.

But the simplicity of life at Athnamulloch is what makes it so special. Stripped of the mindless efficiency of modern life, tasks such as making a pot of tea become slower and more thoughtful. Throughout the week we take turns to cook, and afterwards sit and share the meal together. Living and working communally, bonds are quickly formed, and without the distraction of mobile phones an evening in the bothy hums with positive energy as people chat, read or play cards. Conversation is free ranging and varied, and there’s a real pleasure in coming together with a diverse group who are all united by a common thread of caring for the land. I feel comfortable and at ease, and I laugh a lot.

Each day we fill our planting bags with trees: eared willow, woolly willow, elm, hazel, rowan, birch, bird cherry and aspen. Then bags over our shoulders and spade in hand we set off into the glen to help replenish the land. I love the yellow planting bags. They remind me of the postie’s delivery bag, but instead of carrying letters we’re delivering little parcels of hope into the ground. We learn that the hardest thing about tree planting is not the digging but finding a patch of suitable soil, and as the week progresses, we gradually become more proficient at finding suitable homes for our tiny, precious trees.

We plant on bare wind-swept hillsides and in the sun dappled understory of birch woodland. We learn to tell a Scots pine from a lodgepole pine and spend a day removing the latter to help regenerate the former. We visit an ancient wych elm, a lonely survivor of the ravages of Dutch elm disease and carefully plant seven precious elm saplings in its company.

Before the trip I was worried whether I’d be physically up to the demands of a week of manual labour. But although we are on our feet much of the day, we are always walking and working at our own pace. Together we plant hundreds of trees, and when one person finishes their bag, they turn to help others. Like all life at Athnamulloch, it’s a team effort.

Our guides for the week are endlessly knowledgeable, and share their skills and expertise with such generosity. Walks to the planting site are filled with pauses as their trained eyes spot one thing after another: plants, lichens, mosses, fungi, caterpillars, their joyous enthusiasm for the natural world is infectious. Each day also incorporates time for silent reflection, helping us foster connections with the land that we are tending.

And what land it is. The beauty is so often breathtaking. One morning a cloud inversion hangs in the glen, and as it lifts the world is revealed to be cloaked in spider’s webs. Jewelled with the dew, this usually invisible world hangs delicate and magical. At night I head outside and overhead the sky is drenched in stars. I stand with my neck craned and drink in the wonder of the milky, amorphous swirls stretched overhead. Suddenly out of the dark comes the cry of a bellowing stag, shattering the deep quiet of the glen.

I finish and end each day with a swim, sometimes alone, often with others. The crystal-clear water bites with an icy chill, but the view is phenomenal and the moment when my body relaxes and accepts the cold is sublime. Afterwards I warm up with a cup of tea by the wood-burning stove, shivering and happy.

My week in Glen Affric had a profound effect upon me. Normal life is busy and noisy, constantly demanding attention and action. To step away from it all for a while was a privilege and gave me much needed space and perspective. I learnt a lot – about the damage that we have done to our land, and what we need to do to foster regeneration. The brutally stark difference in vegetation on either side of the deer fences demonstrated without words the devastating impact of overgrazing. But above all it felt good to be part of something positive, working as a group and forming meaningful connections with people and nature. I came away from Glen Affric feeling informed, inspired and hopeful. I very much hope I’ll be back.

Are you also keen to volunteer and make a real difference for nature? Join us for a Rewilding Week to help restore the magnificent Caledonian forest through hands-on conservation activities.

- All

- Blog

- Dundreggan

- Education

- General

- News

- Off the beaten track

- Press Release

- Projects

- Volunteer Voice

- Wildlife